from Derbyshire Heritage

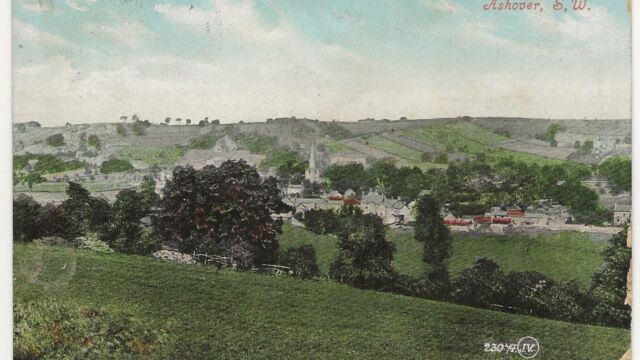

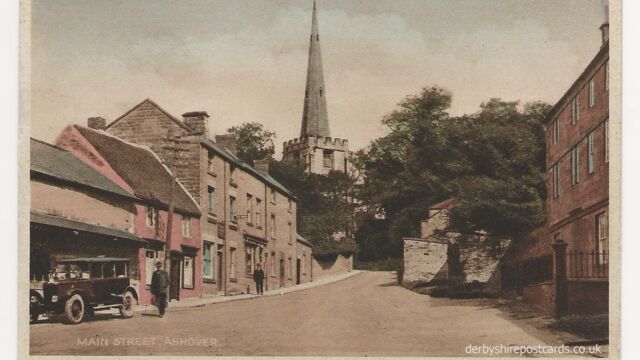

Ashover was situated at the end of the Old Ash Forest and was known in Saxon times as “Essovre”, meaning “beyond the Ash Trees”.

The village was probably in existence when the first ever taxation survey of England was made by King Arthur in 893 but the first written reference to Ashover occurs in the Domesday Book of 1086, in which Ashover was credited with a church, a priest, a plough, and a mill, with a total taxable value of £4.00.

Ashover was a very busy place in the past with lead mines, 13 lime kilns, quarries, coal at nearby Alton, lead smelting at Stonedge, lace thread at Kelstedge, four flour mills on the Amber, shoemakers, nailmakers, basketmakers, stocking frames, cutlery business and rope works.

Lavender, roses, valerian, camomile, and other plants were grown in large quantities, dried, and used for medical and other purposes.

Electricity came to the valley in the 1920’s but it was not until the late 1930’s that Ashover was connected to the National Grid and many outlying farms and hamlets were not supplied until after the Second World War. Gas street lamps were replaced by electric lighting as late as 1967.

During the Civil War Ashover suffered from both the King’s men and the Parliamentarians. The Roundheads destroyed the church windows to get at the lead which they used to cast lead shot and destroyed Eastwood Hall. Fortunately the vicar realised the Roundheads were coming and buried the lead font. The Roundheads, short of ammunition, demolished the windows of the church and used the lead to make bullets. This is now the only lead font to survive in Derbyshire.

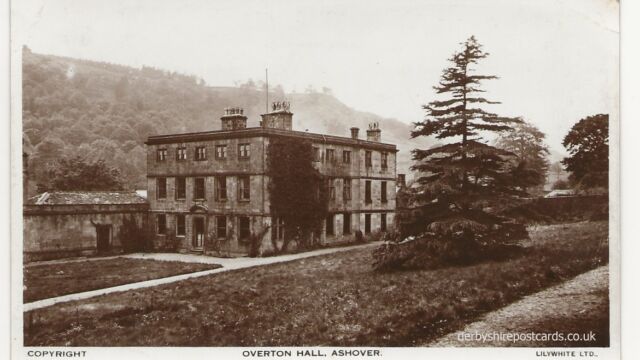

The Royalists slaughtered livestock and drank all the wine and ale in the cellars of Eddleston Hall while the owner Sir John Pershall was away. Job Wall, the landlord of the Crispin Inn, refused them entry, telling them they had already had too much to drink. But they threw him out and drank the ale, pouring what was left down the street.

A Royal Observer Corps post was opened in January 1938 at 299 metres above sea level at a place known locally as ‘Ashover Rock’ a rocky out crop on the ‘The Fabrick’.

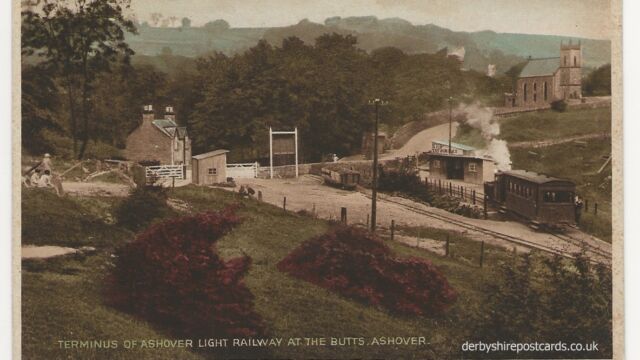

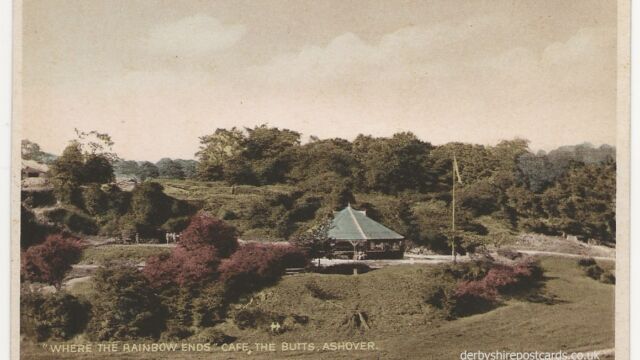

In Medieval times an archery practice field was known as an archery butts, with mounds of earth used for the targets. The name originally referred to the targets themselves, but over time came to mean the platforms that held the targets as well. For instance Othello, V,ii,267 mentions “Here is my journey’s end, here is my butt”. In medieval times, it was compulsory for all yeomen in England to learn archery.

In 1252 the first Archery Law was passed and all Englishmen aged between 15 to 60 years old were ordered by Law to equip themselves with bow and arrows.

A second Archery Law made it compulsory in 1363 for Englishmen to practice their skills with the longbow every Sunday.

Later King Henry I proclaimed that an archer would be absolved of murder if he killed a man during archery practice.

Partly to prevent accidents an area called The Butts was assigned for the archery practice.

They were usually located on common land at the margins of villages and towns usually on a flat area of land up to 200m long. Targets were originally made of a number of circular, turf-covered target mounds with flat tops ranging between 2m to 8m across and 1m to 3m in height.

Several English towns have districts called “The Butts”, but they may not always take their names from archery. The Middle English word “butt” referred to an abutting strip of land, and is often associated with medieval field systems.

The word is also used today for the earthwork mounds on, or before, which targets are mounted on a rifle range, with the object of stopping the flight of bullets beyond the range.